The first time I heard Transatlanticism, it awoke me from a deep sleep.

This sounds poetic, and perhaps it was. But truth be told, I was, in fact, asleep when the compact disc started spinning in my bedside alarm clock (this is a throwback article, after all). It had been given to me by a friend the previous night, and as I turned to look at the time and hit the snooze button, that same friend rolled over in bed to prevent the track from pausing.

Well. Good morning.

It was a cold Saturday in college, rainy and gray as the light of dawn emerged. There was a feeling of uncertainty in the air, of questions that didn’t want to be asked and answers that didn’t want to be heard. The alarm had been set the previous night to allow us to avoid detection from housemates and friends, consequences put off for a later time that wouldn’t be soaked in the hangover from a weekend party. We laid there briefly, but lingering further could have proved troublesome. As a secret liaison slipped out the back door, the south end of the campus remained dormant. It was a terrible time in my life; I needed someone to be close to, but couldn’t possibly return the affection. I walked back upstairs, and the album played on.

Yeah she was beautiful, but she didn’t mean a thing to me.

Nearly every time I hear the opening power chords and cymbal crashes to ‘The New Year’, I am drawn back into this moment, one of conflicted motives and confusing emotions. I cannot thing of a single more appropriate, contemporary sequence of songs to serve as the soundtrack to the ebb and flow of a doomed tryst between two friends with vastly different approaches to such a situation. The protagonist singing these eleven tracks is flawed, but in a wonderfully complex way.

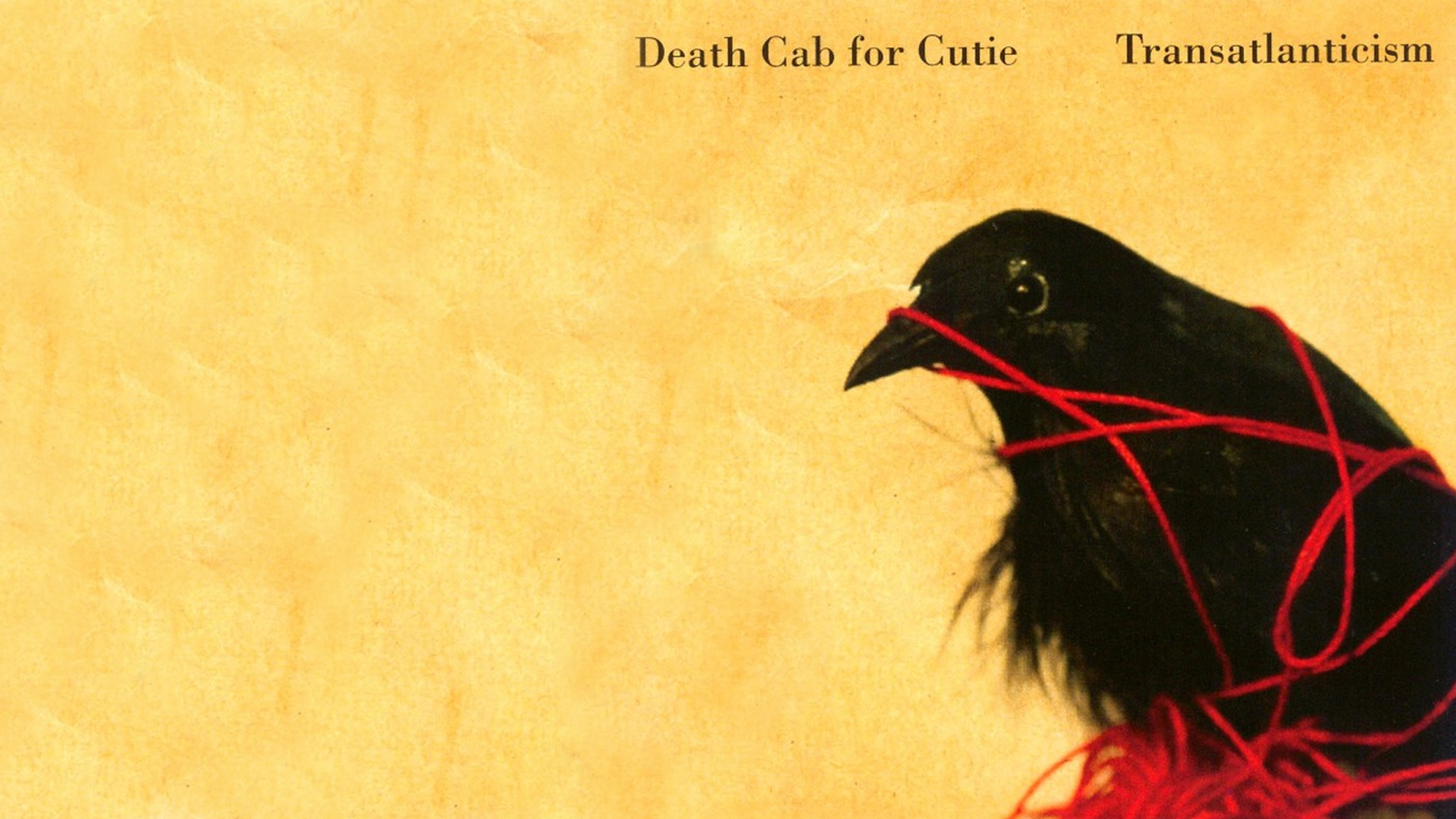

A short time ago, Death Cab For Cutie announced it would be playing Transatlanticism in its entirety during its Bumbershoot set, and subsequently added another show in which the same performance would occur. This is all in honor of the ten-year anniversary of the album, and it’s a mildly remarkable thought in itself that nearly a decade has passed since its release date.

One of the first things that sets Transatlanticism apart from other records of its genre is that it isn’t merely a series of isolated tracks played in succession, but a consistent motif of interrelated songs constructed into a congruent album. There is a feel to it all, sensed in every purposeful note and ambient sound. It’s a phenomenal recording for a rainy day, the mood it projects as cloudy as the decision-making in the words and phrases of the lyrical lines.

So this is the new year, and I don’t feel any different.

This album was clearly written by a young person, rife with themes of growing older but not understanding how to effectively grow up, embracing passion and impulse but unable to convert these actions and emotions into sustainable, healthy relationships. It’s a back-and-forth battle between the head and the heart, of knowing the right thing to do but struggling to convince oneself to go through with it, the instruments skillfully playing their parts in accenting – if not carrying – the meaning of the spoken words in each song. Consider this: the title track of the album is just shy of eight minutes long, but contains only ten unique lines of lyrics, one of which is simply, “So come on”. One need not have a firm grasp of the English language to understand what Ben Gibbard is saying; frequently, the music speaks for itself.

I’ve got a hunger twisting my stomach into knots.

The core of the album is found in tracks 5-8, both the most artfully crafted songs on the disc and also an ongoing narrative running the gamut of emotions – satisfaction and shame, attachment and distance – that I could all-too-easily relate to in the weeks that followed that rainy morning so long ago. I’ve always found it interesting that the one track on the record that actually feels happy is the one that’s essentially about giving up, but ‘The Sound of Settling’ is exactly that, an ode to embracing a dire situation and frankly, not caring. Of course, this begins to change rapidly in ‘Tiny Vessels’, as a feeling of guilt begins to creep into something that previously seemed easy and uncomplicated – am I being carefree or careless? Once this decisional analysis kicks in, we’re back to the juxtaposition of deep loneliness in the face of companionship, the forlorn repetition of the phrase “I need you so much closer” found in ‘Transatlanticism’ connected to the uncertainty of ‘Passenger Seat’ by simplicity of song structure and an underlying atmospheric hum found in both tracks – there’s something here, but it seems so far away. As the final notes of the latter song fade away, however, we’re greeted with something we haven’t yet experienced at this juncture – hope.

Of course, a great album of the past is nothing without the memories of experiences it evokes, the immediate transportation to a different time where it served as one’s soundtrack. ‘The New Year’ still brings me back to that aforementioned college weekend. ‘The Sound of Settling’ reminds me of a hot summer night on the lawn of Merriweather Post Pavilion. ‘We Looked Like Giants’ accompanied the drive my friends and I would take through the snowy Catskills on the way back to school for spring semesters. But perhaps the strongest association I have with any of these songs came in a slightly different form. I was in rural Ohio for a clinical one summer when the sky of a sunny, humid day suddenly turned black. It wasn’t long after the “Code Gray” was called that three tornadoes ripped through town, uprooting trees and collapsing hotels as they came perilously close to the hospital in which I found myself. As we hunkered down with sick patients and crying children, windows buckling and the power failing, I found myself softly whistling the piano notes of ‘Passenger Seat’ as a means of trying to remain calm; there was uncertainty that day, but there was hope. And I know in my heart that I am in no way alone in holding these type of connections to this collection of songs. I’m certain there are countless other anecdotes from strangers in faraway places that are just as connected to Transatlanticism as anything I could possibly say. This album means a lot to me, as I’m sure it does to many of you as well. A decade has passed since it arrived, but its resonance has yet to fade.

When you need directions, then I’ll be the guide.

About Andrew Rose

Andrew Rose is a writer and editor for Rookerville. He also manages a travel blog for his friends and family. His book, “Seizure Salad”, is a work of fiction - not in that it is a tale of fantasy, but in that it does not actually exist.