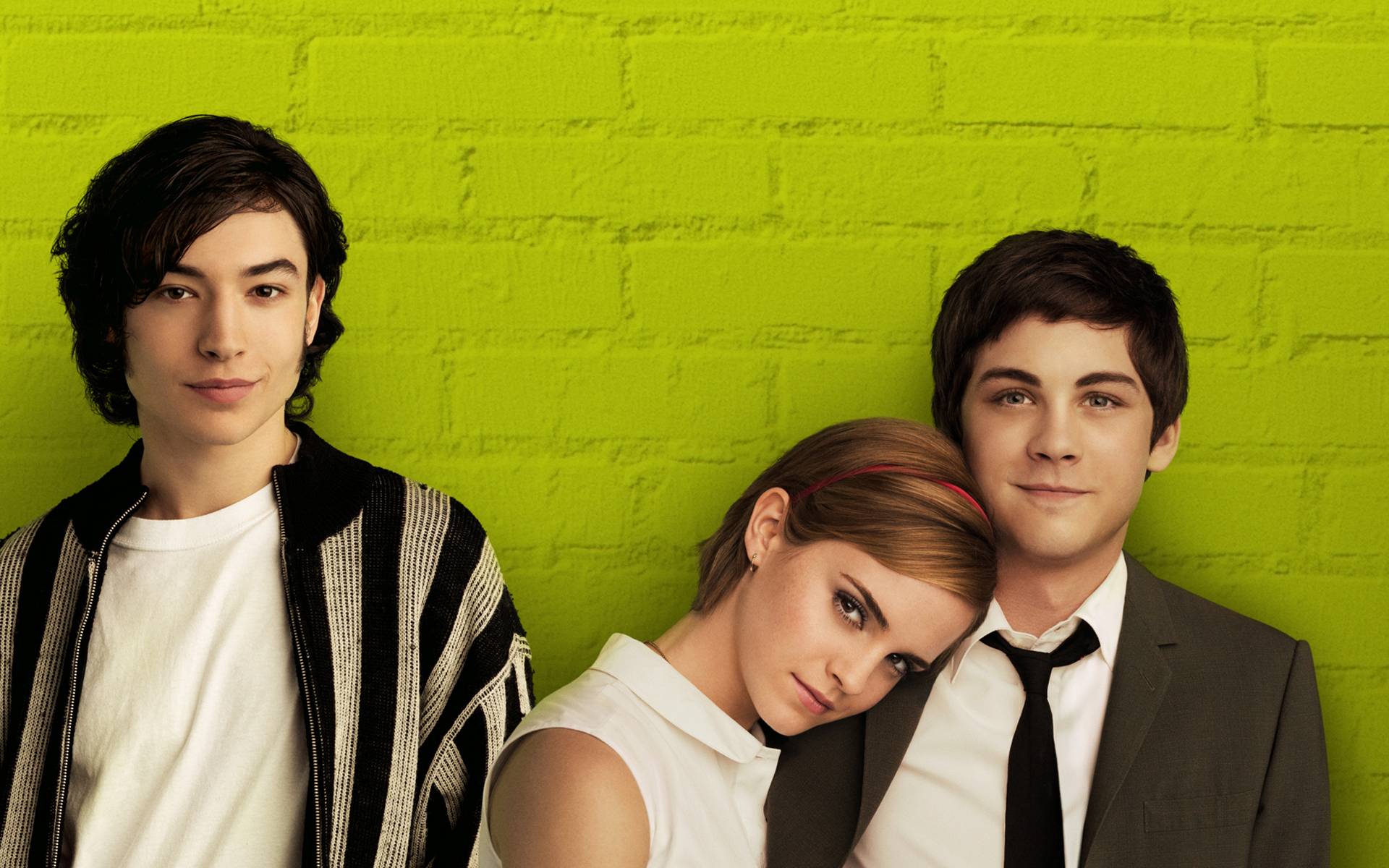

Consider one scene in particular, the way it’s portrayed in the book and the 2012 cinematic adaption. Charlie (Logan Lerman), Sam (Emma Watson), and Patrick (Ezra Miller) leave a party one night, in the first blush of friendship. The trio drives around aimlessly, as teenagers are wont to do, and as they approach a tunnel, a song pops on the radio. None of the three of them have ever heard it, but are instantly smitten with how it sounds. Sam tells Patrick to turn it up. She sticks her head out the sunroof to feel the wind blowing through her hair as the music blows past her. In the book, Charlie refuses to tell us what the song is, his reason being that we won’t be able to get why the song is so great unless “you’re driving through a tunnel with your two best friends on the night of your first big party.” The film, on the other hand, plays the song for us—it’s “Heroes” by David Bowie.

The difference between those two scenes says it all here, both in a general sense (books allowing a reader to imagine what’s happening, films turning the audience passive by supplying the experience for you) and more specifically. On the one hand, the scene is handled surprisingly well—a shot of Watson that doesn’t last too long that then cuts immediately to the next day without fanfare. On the other hand, the effect is spoiled now that we know the song. It’s not the song itself; obviously I’m more apt to like characters who revere Bowie than ones whose lives are changed by, say, the Shins. But I’m also more apt to like characters who’ve at least heard of Bowie, rather than considering themselves arbiters of musical taste while being evidently unable to even find out who sings one of his most mainstream hits.*

Stephen Chbosky’s Perks of Being a Wallflower came out in 1999, when I was the age of the narrator. It was wildly popular, not because it’s well-written or anything (it’s not) but because it was published by MTV Books, and MTV had actual TV commercials advertising the thing to impressionable teenagers like me. It worked, too; I bought it and liked it very much.

Well, of course I did. You have to be fifteen, have to have not read very much else, to think it’s any good. Since Chbosky also wrote and directed the film (a rare privilege for an author), I know it’s strange to differentiate how the book views these characters vs. how the film does, but I think it’s fair in this case. There were fourteen years between the one and the other, and writing a book about high school in your twenties (as Chbosky did) is a very different animal than directing a film about high school in your early forties (ditto). The book suffered from Chbosky’s youth and inexperience, but what charm it had, ironically, stemmed from that same place. There’s something fragile and innocent about book Charlie discovering how to masturbate but refusing to ever think about Sam, his crush, out of respect for her. There’s something accurate in a way high school films never quite accomplish in the way that book Charlie is never bullied at school, merely ignored: my memories of high school don’t include the hierarchical caste-system of nerds-jocks-freaks-stoners we’re always pummeled with in cinematic representations of high school. There’s something subtle about book Charlie’s father as a man who never expresses his emotions to his family, but weeps like a baby at the series finale of M*A*S*H. And, yes, there’s something kind of sweet about a kid who doesn’t want to spoil the experience of a song by telling you what it is.

The film finds Chbosky far-removed from the days of high school, so all of those little coming-of-age kernels are gone. Obviously the masturbation stuff is out, and I already told you about the song thing. But also his father is played not by a schlubby, removed Jack Arnold-type but by Dylan McDermott, attractive and slick and not at all right for the part. Film Charlie is indeed bullied, called “faggot” by the girl who sits next to him in class, kidnapped and thrown into the bathroom by a group of kids (which makes no sense, since he’s given to bouts of rage, as we see at the end when he saves Patrick). Worst of all is that there’s a fetishization, perhaps borne of the new national tendency toward anti-intellectualism, of apathy. Where the book’s title was ironic (there were no perks; Charlie had to learn to quit sitting on the sidelines), the film takes the title at face value. “I’m below average!” exalts Patrick when he gets a C- (fuck you, grades!). Sam has to take the SATs like three times before getting a halfway decent score (fuck you, standardized tests!). The aforementioned girl who calls Charlie a faggot “has gotten straight A’s since kindergarten” (fuck you, honor roll!—what happened to the days when our high school cliché was that the popular people were stupid and the losers were smart? I long for Revenge of the Nerds). The book saw their weird group of friends as actually weird, resigned to hanging out at places and times no one could see them (basements, garages, midnight screenings of underground films). The film actively agrees with them though, seeing them as not weird but misunderstood, waiting patiently until mean old high school is over so that they can be appreciated by smarter people (one girl gets into NYU film school (!) based evidently only on the fact that she’s seen The Rocky Horror Picture Show).

Which, again, has everything to do with Chbosky now being too old to remember high school with any accuracy, and so instead selling us a commodified version of that world. But the film is actually much better than the book, for much the same reason. Now that Chbosky’s an adult, he’s at least got the benefit of perspective, and (for the most part) ditches the epistolary stuff so that the images can speak for themselves, instead of being spoon-fed to us by Charlie’s (pretty grating) narration. Also, he’s gained confidence as a storyteller (no, seriously) in the intervening years. The biggest problem with the book was that Chbosky didn’t trust Charlie to be merely a misfit so instead made him a Victim, throwing problem after problem after problem on the kid: his best friend killed himself, his sister was abused by her boyfriend, his aunt and mother had been abused by his grandpa, he witnessed a rape at a party as a kid, he’d been sexually molested by his aunt, his new best friend was a closeted gay man, his new crush had been assaulted by a friend of her father, he had a chemical imbalance, etc etc etc. But what Chbosky the author lacked in confidence, Chbosky the director makes up for by narrowing those problems down to only like three, and even then they’re impressively underplayed (the Big Reveal with the aunt, especially, could have been maudlin but instead gets explained through a series of jump cuts, and he even has the good sense to hire Joan Cusack as the psychiatrist at the end).

Bottom line: the film is way better, which is to say it’s average as opposed to below average (“It’s below average!” Patrick might have exclaimed approvingly of the novel). Maybe in the end the point is just that I’m old and have myself lost touch with the sensibilities I had in high school. But also, I think, that’s a good thing.

*Unless this is supposed to be some weird in-joke or something, since the song was eventually covered by the Wallflowers (ha ha?). My point still stands, though.

About Ted McLoof

Ted McLoof is a writer at Rookerville and teaches fiction at the University of Arizona. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in the Minnesota Review, Bellevue Literary Review, Gertrude, Monkeybicycle, Sonora Review, Hobart, DIAGRAM, The Associative Press, and elsewhere.He's recently been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and a Best of the Net Award. He is very cool and very handsome and he'd like to buy you a drink.